This blog was originally published by the World Economic Forum

By Silvia Montoya, Director of the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) and Dankert Vedeler, Co-Chair of the SDG Education 2030 Steering Committee and Assistant Director General of the Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research

Driving systematic change in critical areas such as health, energy and infrastructure is the task of the Global Future Council's 700 members in Dubai this week. They are investigating how breakthrough technologies can be used to "join the dots".

One key prerequisite for such change is a global population that is well-informed, well-educated, and literate. This is essential for progress towards Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) on education, for example. But many other SDGs also depend on populations becoming literate and numerate.

Education can cut the poverty rate by half

Take poverty, for example. The global poverty rate could be reduced by more than half if all adults completed secondary education, according to estimates published in a joint paper by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics and the Global Education Monitoring Report. And take the chances of decent employment. Skills and jobs for young people feature prominently in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. SDG target 4.4, for example, calls for a substantial increase in the number of young people and adults with skills relevant for employability.

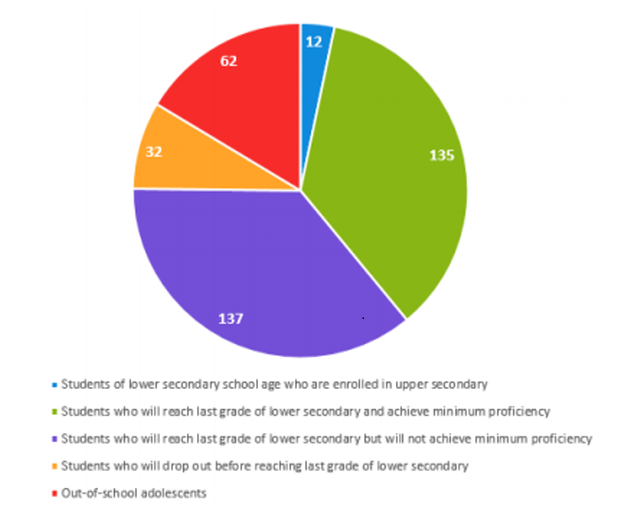

But recent data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics has raised concerns about the prospects for 617 million children and adolescents who are unable to read properly or handle basic mathematics. Right now, only half of the world’s children achieve minimum proficiency in reading and mathematics by the time they leave school, according to a new global composite indicator, developed by the UIS. A total of 230 million adolescents will not achieve minimum proficiency levels in reading and mathematics by the time they should be completing lower secondary education. While many of them are out of school, about 60% or 137 million are in classrooms, as the chart below shows.

Alarm bells ringing

The data have caused alarm about the number of adolescents and young people who leave school without the basic skills they need for the 21st century workplace. We face a global learning crisis, and the prospect of a lost generation of young people who should be forging the economic and social capital of their countries, but who lack the skills to do so.

Figure 1. Distribution of lower secondary students by school exposure (in millions)

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics

The future of any economy depends far more on its human resources than its physical assets. However, the young people who represent the world’s most dynamic human resources are almost three times more likely to be unemployed than adults. Today’s young people (aged 15-24) make up 18% of the global population, but 40% of the global unemployed.

Those who are in work often find themselves trapped in lower-quality jobs. Young women are more likely to be underemployed and under-paid, and to take on part-time or informal or temporary work. As stated by the International Labour Organisation, economic growth, development and stability largely depend on the education, training and employability of youth. When young people are not engaged in the education system or the labour market, they become disconnected from society, gradually losing any prospect of developing new skills that could help them find meaningful employment.

The rising demand for skills

According to the Education Commission, some 40% of employers globally are already finding it difficult to recruit people with the skills they need. If education in much of the world fails to keep up with the rising demand for skills – with reading, writing and mathematics considered a bare minimum – there will be major shortages of skilled workers in both developing and developed economies as well as large surpluses of workers with poor skills. Without urgent action, more than a quarter of the population in low-income countries could still be living in extreme poverty in 2050.

The global learning crisis poses a major threat to future prosperity. But this doesn’t have to be the case. It is not inevitable. We can ensure that all children and young people are in school and learning the skills they need to be successful in work and life. This vision is achievable within a generation if all countries accelerate their progress to that of the world’s top 25% fastest improvers in education, according to research by the Education Commission.This vision is firmly endorsed by the UIS and in common with the SDG Education 2030 Steering Committee. But it will stand or fall on the availability of more and better data.

The world’s ultimate renewable resource is its children and young people. New data from the UIS has reinforced calls for far greater investment in them. The task ahead is to push for that investment urgently, drawing on the best possible data to ensure that every child has the skills for a productive future.

What will it take to produce the best possible data? As the official source of SDG 4 data, the UIS works with countries around the world on a daily basis, helping them to produce the data that are needed. The UIS understands the technical problems that face statisticians as they strive to provide the quality of data needed by policymakers. While sounding the alarm for the best possible data, the UIS is also making the case to strengthen the capacities of countries in the upcoming edition of the UIS Sustainable Development Digest, a source for the latest data strategies and tools.

Leave a comment