By Aaron Benavot, Director of the Global Education Monitoring Report, and Silvia Montoya, Director of the UNESCO Institute for Statistics

In a few weeks, the UN High-Level Political Forum will gather to discuss poverty eradication as a cornerstone of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Agenda. Debates over how to tackle entrenched poverty often centre on different political ideologies. For some, the answer may be the pursuit of free-market economic growth, in the hope that some of the wealth generated will ‘trickle down’. For others, the answer may be social and economic interventions aimed at levelling the playing field, where everyone has something, even if that something is – at best – meagre.

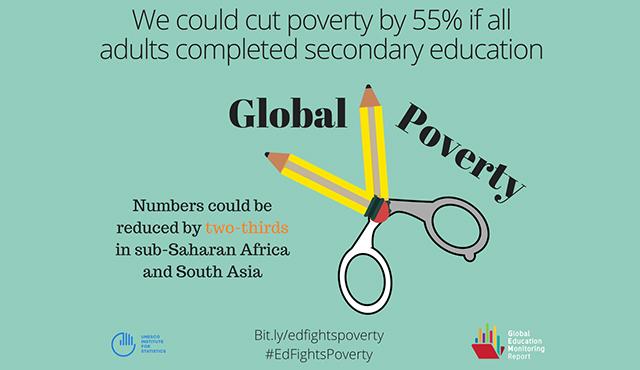

A new paper released today by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) and the Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report moves this debate beyond politics. It shows that the global poverty rate could be more than halved if all adults completed secondary school.

The paper, Reducing global poverty through universal primary and secondary education, demonstrates the importance of education as a lever for ending poverty and helping improve the lot of adults currently living under the threshold of $1.90 a day . By confirming the links between the two, the paper is welcome news for those working to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal on poverty eradication by 2030 (SDG 1) while reinforcing the investment case for universal secondary education – an education target under SDG 4.

420 million people could avoid poverty if all adults completed secondary education

The new paper builds on the average impact of education on growth and poverty reduction from 1965 to 2010 in developing countries to reveal that nearly 60 million people could avoid poverty if all adults had just two more years of schooling. If all adults completed secondary education that number would increase seven-fold, and 420 million people could be lifted above the poverty threshold. That is enough to cut the total number of poor people in half worldwide, and by almost two-thirds in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

The numbers would fall because education provides people with the skills they need to boost their employment prospects and their incomes, while helping people to protect themselves from the worst impacts of poverty during hard times. And a more equitable expansion of education is likely to reduce inequality, lifting the poorest people from the bottom of the ladder.

The good news is that ensuring that every adult completes a good quality secondary education is a perfectly feasible and achievable ambition, with the right choices and the right levels of well-targeted investment. The bad news, as the paper shows, is that the number of children and youth out of school remains high in many countries, making it unlikely, if current trends continue, to meet the global education targets for generations to come.

No progress in reducing out-of-school rates

There has been virtually no progress in reducing out-of-school rates in recent years for both primary and secondary age groups. The world has yet to make good on its promise to achieve universal primary education, which was supposed to occur by 2015. Globally, 9% of all children of primary school age are not in the classroom. And the gaps get bigger as children get older, with 16% of youth of lower-secondary school age missing out on education, rising to 37% for those who should be in upper secondary school. In total, 264 million children and youth were out of school in 2015.

One of the regions where universal secondary education could have the greatest impact on poverty, sub-Saharan Africa, remains the region with the highest out-of-school rates for all age groups. More than one-fifth (21%) of children aged 6 to 11 are out of school, rising to more than more than one-third (36%) of adolescents aged 12 to 14 and half (57%) of all youth aged 15 to 17.

The paper confirms that education must reach the poorest to enable them and their families to lift themselves out of poverty. But this is yet another story of inequalities. Children from the poorest 20% of families are eight times as likely to be out of school as children from the richest 20% in lower-middle-income countries. And in the world’s poorest countries, children are nine times as likely to be out of primary and secondary school as children in the richest countries.

While calling on countries to improve the quality of education as part of efforts to get all children into school and learning, the paper also stresses the need to reduce the direct and indirect costs of education for families, including school fees, and costs of textbooks and uniforms. UIS data confirm that out-of-pocket expenses for families remain high even at the primary level in many countries. In Ghana, for example, households spend about $87 each year for every child in primary education – a figure that rises to $151 in Côte d’Ivoire and to $680 in El Salvador. Such costs, particularly for the poorest families, can be simply too heavy to bear.

To reduce the financial burden on families, the paper highlights policy solutions to keep children in school, including school-feeding programmes, cash transfers, and complementary health interventions. It also calls for more targeted efforts to safeguard the right to free education among all marginalized groups, such as children with disabilities, refugee and migrant children, and those affected by gender discrimination (whether girls or boys).

Could there be a more cost-effective (and non-political) way to make a dent in global poverty than education? We hope this can be on the table at next month’s High-Level Political Forum at the UN. If the delegates cannot agree on everything, they can surely agree on investment in secondary education as a practical way to ensure that people no longer have to survive on barely two dollars each day.

Leave a comment