By Silvia Montoya, Director of the UNESCO Institute for Statistics and Dankert Vedeler, Co-Chair of the SDG Education 2030 Steering Committee

This blog was also published by Norrag.

The global goal for progress on education (SDG 4) has been set: an inclusive and equitable education for every child by 2030. The individual targets that must be achieved if we are to reach the goal are in place, from learning outcomes to teacher training. And experts and organizations working on education data have developed the detailed indicators that will signal whether or not the world is on track to achieve the global goal by the deadline.

So researchers and statistical offices worldwide know the final destination, the route-map and the milestones along the way. Surely it is just a matter of scooping up the required data, crunching the numbers, and plotting a neat and smooth course towards 2030? Wrong. We can have the clearest goals, the best methodologies and the most perfect indicators, but we’re not going anywhere without the data.

The UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), which is in daily contact with national statistical offices and line ministries around the world, knows only too well that the lack of data – and of the capacity to gather and analyse data – risks holding back global progress on education.

We see two meetings this week in New York – the High-level SDG Action Event on Education and the Third Meeting of the SDG-Education 2030 Steering Committee – as opportunities to put this crucial issue on the table and make the case for far greater investment in data.

To say this is urgent is an under-statement. Right now, we have only one-third of the data we need worldwide to tell us whether all children are reaching a minimum level of proficiency in reading and mathematics (Table 1).

Table 1: Data availability for Indicator 4.1.1: Proportion of children and young people in Grade 2 or 3; at the end of primary education; and at the end of lower secondary education achieving a minimum proficiency level in reading and mathematics

|

Region |

|

|

Arab States |

24% |

|

Central and Eastern Europe |

64% |

|

Central Asia |

33% |

|

East Asia and the Pacific |

15% |

|

Latin America and the Caribbean |

29% |

|

North America and Western Europe |

61% |

|

South and West Asia |

8% |

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

26% |

|

World |

33% |

Source: UIS Database, June 2017

Data coverage falls to just 27% for access to quality early childhood development, including pre-schooling. And it gets worse: just 18% coverage for technical and vocational skills, and 12% for data coverage related to youth and adult literacy and numeracy. And when it comes to SDG target 4.7, on whether learners have the knowledge and skills they need to promote sustainable development, data coverage is precisely zero.

What’s more, we cannot assume that good data coverage means good quality data. Overall, even when countries report data, the coverage varies across questionnaires and regions.

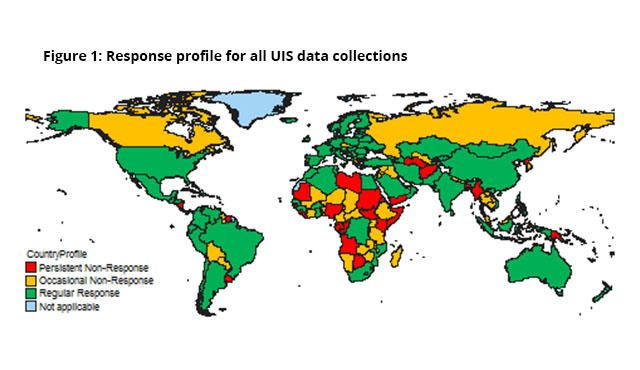

An assessment of the UIS key performance indicators confirms that countries and regions are at different stages of development in terms of their capacity to respond to UIS annual surveys in all fields (education, science, culture and communications). We have found that while 98 countries regularly respond to all of our surveys and about 50 countries generally respond but not always. Yet as shown in Figure 1, 63 countries rarely respond, including 15 of those which never respond at all. Sub-Saharan African countries face the greatest data challenges.

Figure 1: Response profile for all UIS data collections

Responding to a questionnaire is just the first part of the process. Are countries providing all of the information needed to produce international indicators? About 23 countries provide nearly all the necessary data for key education indicators (identified by the UIS to track data data quality). Yet the coverage for about 43 countries is less than 45%.

Changes in reporting patterns over the past 10 years indicate problems with sustaining regular responses, and there are also issues around timeliness. UIS surveys are aligned to national reporting cycles to collect the most recent data available at national level. We compare the age of the data when it is submitted to us as compared to the reference year, and the younger the data the better. While most countries report data within 12 months of the reference year, some struggle to provide timely statistics.

The UIS works directly with countries to tackle chronic national data gaps on education. We understand their data challenges and when they need help – from completing a survey to tools to improve the production, quality and use of their data – they come to us. We also work directly with the people producing the data – the statisticians – and those who use the data for education policymaking and planning.

We have advanced the debate on who spends what on education at national level – highlighting the burden of spending by families, for example – to get a full picture of education finance around the world. As well as working directly with countries to compile education expenditure data through our annual surveys, we help them to improve their national statistical systems and adopt new methodologies.

We help countries improve their data on out-of-school children, stressing the need for consistency, with current variations between different types of estimates skewing the numbers – often by millions – depending on the data source.

We build alliances at the global level, working on state-of-the-art methodologies and standards to generate the data needed to reach the education goal. Over the past year, for example, UIS is leading the Global Alliance to Monitor Learning (GAML) and co-chairing the Technical Coordination Group on SDG 4- Education 2030 Indicators (TCG).

And we develop new ways to use existing administrative and household survey data to develop indicators on equity, which lies at the heart of the SDGs. As the official source of SDG 4 data, the UIS has established the International Observatory on Equity and Inclusion in Education to foster and develop the methodologies, guidelines and research needed to build a global repository of data and standards to measure equity in education. This information is vital to help countries, UN partners and civil society groups to effectively reach the most marginalised groups.

The bottom line is that national and global development goals will remain just goals without data to keep all stakeholders accountable. That takes money.

To maintain its current data services, the UIS needs $10.5 million each year. But the SDG agenda requires far more – and far more detailed – data than anything that has gone before. And if the UIS is to develop the methodological tools and produce all of the SDG 4 global and thematic indicators, it needs $13.5 million per year. Far from seeing its funding increase at this crucial time, the UIS is facing a budget crunch that threatens its operations, just as the global demands for its data are escalating.

The international education community – from countries and UN agencies to donors and civil society groups – relies on UIS data to direct policy, set targets, drive advocacy and monitor progress. Our hope is that the international education community will recognize the need to preserve and increase the support we can offer.

Leave a comment