By Silvia Montoya, Director of the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS)

It seems so obvious: without good teachers, there cannot be good education. But when you look more closely at the conditions in which millions of them work, you could be forgiven for thinking that this message isn’t getting through.

The latest data release from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) offers some sobering facts and figures for the annual CIES Conference in San Francisco this week. The Conference will focus on ‘Education for Sustainability’, and it seems to me that you cannot sustain anything in education – not even one single school class – without a good teacher who is driving the pupils’ learning.

The big question is: are we supporting our teachers to be as good as they can? According to UIS data in our eAtlas of Teachers, the answer ranges from maybe to not really. So, what do teachers need to ensure good learning?

1. Teachers need to be properly qualified and trained

More than half of children and adolescents worldwide – or 617 million – are not learning basic skills in reading and mathematics according to UIS data, which show that the vast majority are in school.

Quality education begins with qualified teachers who deliver good lessons so that students can learn. This is why Sustainable Development Goal 4.c (SDG 4) calls on countries and development partners to substantially increase the supply of qualified teachers by 2030.

To measure progress towards this target, SDG Indicator 4.c.1 tracks: the proportion of teachers in: (a) pre-primary education; (b) primary education; (c) lower secondary education; and (d) upper secondary education who have received at least the minimum organized teacher training (e.g. pedagogical training) pre-service or in-service required for teaching at the relevant level in a given country.

As a statistician, I cannot help but see a mismatch between the target, which refers to qualified teachers, and the indicator, which refers to minimum teacher training. Countries have different definitions of what it means to be ‘trained’, making it difficult, if not impossible, to draw international comparisons. Some countries require an advanced university degree that can span five years of education. For others, a three-month training program seems to be enough.

So the data must be treated with caution: an impressive-looking proportion of trained teachers in one country could mask lower requirements than another country. This is why the UIS is working with partners, including Education International, the UNESCO Teachers Task Force and the Global Partnership of Education, to develop standards to compare teacher qualifications across countries.

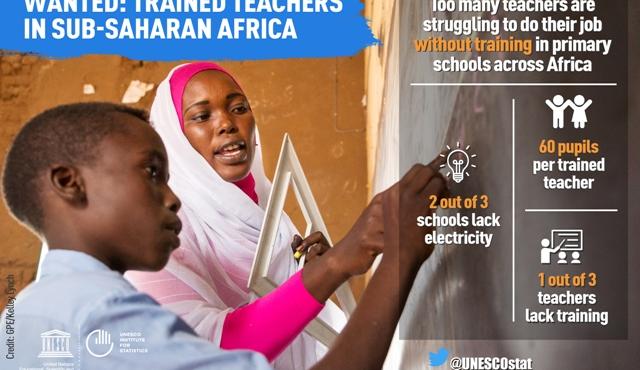

While the methodological work continues, the data clearly show that sub-Saharan Africa has the lowest percentages of trained teachers (see Figure 1). It is also the region with the lowest levels of learning.

Figure 1. Percentage of trained teachers in primary education

Moreover, the percentage of trained teachers has been steadily falling across sub-Saharan Africa. In 2017, 64% of primary teachers were trained compared to 85% in 2000. At the secondary level, the rate fell from 79% in 2005 to 50% in 2017. During this period, many countries in the region undertook a massive expansion of their education systems and hired more trained and untrained teachers. So while the rates of trained teachers fell, it is possible that the actual number increased.

2. Teachers need to be properly paid

Teachers deserve salaries that recognize their unique contribution to the well-being of entire societies. On the finance side, we do not have enough data to draw regional averages, but we do have some national data on teacher salaries as a percentage of total education expenditure. According to the latest available data (2017), the percentage in low- and middle-income countries ranged from more than 72% in Guatemala to 42% in Peru.

However, just because countries devote a great deal of their education spending to teachers it does not mean that those teachers are getting the pay they deserve, especially when they face very difficult working conditions, as reflected by pupil-teacher ratios (PTRs).

3. We need enough teachers to reach all children

Which brings us to the third component needed for sustainable teaching: a sufficient supply of good teachers. UIS data show an extraordinary range of pupil-teacher ratios around the world, from an astounding 58 primary pupils per teacher in Rwanda to just 9 in Cuba. Of the 20 countries with the highest number of pupils for every teacher, 16 are in sub-Saharan Africa.

While smaller ratios in the world’s richest countries and massive ratios in the poorest countries are no surprise, a number of low- and middle-income countries manage fairly well. Costa Rica, Georgia and Lebanon, for example, have a dozen or fewer pupils for every teacher. But what is clear is that many countries desperately need more good teachers who deliver effective lessons– and particularly at the primary and lower secondary levels where children need more one-to-one support.

4. Teachers need decent classroom conditions

Finally, we have to consider the classroom conditions facing teachers and their students. Imagine teaching a class of more than 50 pupils without electricity, drinking water or access to basic handwashing facilities and toilets?

The latest UIS data on SDG Indicator 4.a.1 show that far too many teachers are facing some dire classroom conditions. For example, two out of three primary schools in least developed countries don’t have electricity and only 43% have handwashing facilities. Less than half of primary schools in sub-Saharan Africa have access to clean drinking water let alone access to Internet or computers.

The UIS is working to close the data gaps and improve the indicators

While working with countries to improve the availability of data, we are also developing new methodological approaches to improve the comparability of indicators on teacher training and qualifications. We will present the latest developments in methodological work at the CIES on Thursday, April 18 (10:00-11:30 a.m.), during a session entitled Teacher Autonomy.

In the medium term, we aim to develop a new classification for teacher training programs and qualifications, similar to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) that was developed to make education programs comparable across countries. However, the creation of a new classification for teacher training will take some time to develop and to gain traction at the national level.

To this end, we are also working with UNESCO’s Section for Teacher Development and the International Task Force on Teachers for Education 2030 to consult experts from countries and partner organizations to forge a consensus on what it means to be a qualified teacher. Taskforce partners, including the GPE, have made a call for action to “intensify efforts to develop robust definitions and classifications of qualitied teachers and strengthen cooperation and reporting mechanisms to ensure full monitoring of SDG target 4.c.”

We need to move fast: a review of all SDG 4 indicators in 2020 will demand that each one has a fully-developed methodology or it risks getting removed from the measurement framework.

As the go-to source for SDG 4 data, the UIS works closely with countries and partners to improve data on teachers and makes the case for greater investment in both data capacity and its use to inform policies and practice. We believe that robust data on the situation of teachers can help them to do their vital job for children and for societies.

This blog was also published by the Global Partnership for Education (GPE).

Join the UIS at the following CIES events:

Leave a comment