By Friedrich Huebler, Head of Education Standards and Methodology, UNESCO Institute for Statistics

This year’s International Literacy Day celebrates multilingual education

It is your very first day at school. You’re excited. Perhaps even a little nervous? What is this special day going to bring? Above all, what will you learn?

Your teacher arrives and says hello. But after that, you struggle to understand what she is saying. It is not because you’re stupid – you’re smart. It is because she is not talking in the language you use at home, with your family or when you are playing with your friends. So you mimic the other children around you, opening the books when they do, turning the pages when they do. But it seems that that this day is not going to be so special after all.

Over the months and years, you study really hard and eventually make up the lost ground. But it is a struggle having to work so much harder than everyone else, just to catch up with them.

We know that the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) – a quality education for all – demands linguistic diversity in education and adult literacy. And, frankly, anything that helps to tackle the world’s literacy challenges has our full support.

Our most recent projections broadly reflect those challenges, which undermine the prospects of achieving SDG 4 by its deadline in 2030. SDG Indicator 4.6.1 focuses on the proportion of the youth and adult populations that achieve a fixed level of proficiency in functional literacy and numeracy. The problems is that, for the most part, only high-income countries are currently able to produce the data, so reporting for most developing countries is limited to traditional youth and adult literacy rates. These traditional data are very limited from a policymaking perspective because they are largely based on self-declared information gathered by censuses or household surveys in which the head of household or another respondent is asked how many people in the family can read and write.

As the custodian agency for SDG 4 data, the UIS works with partners through the Global Alliance to Monitor Learning (GAML) to address measurement challenges based on consensus and collective action, while improving coordination among actors. While developing the standards and methodologies to produce internationally comparable data, the UIS is also working to improve the availability of data by expanding the options available to countries. In particular, the UIS has developed Mini-LAMP, which is specifically designed to offer a cost-effective approach for to low- and middle-income countries. Mini-LAMP can be easily adapted to meet their policy needs and budgets. For example, Mini-LAMP can be used as a stand-alone assessment tool or integrated into a household survey – a flexible and streamlined approach that enables countries to reduce the operational and technical costs associated with learning assessments.

One in three young people cannot read in low-income countries

According to current UIS data, the global youth literacy rate stands at 91%. But when we look closer, we see that this leaves 102 million youth worldwide unable to read and write a simple sentence. In low-income countries, one in every three young people cannot read. And there are still 750 million adults (two-thirds of them women) who lack basic literacy skills – equivalent to more than twice the population of the United States.

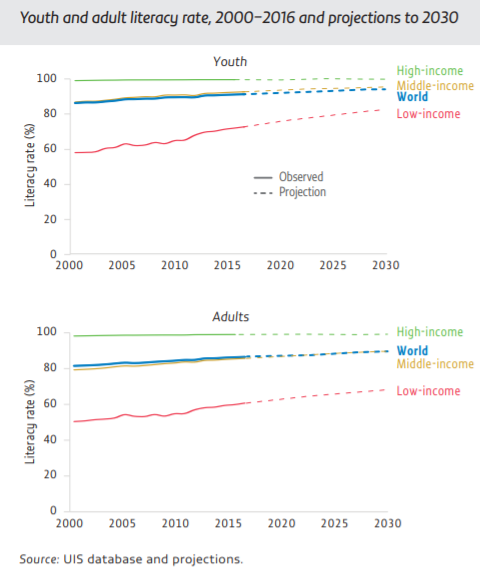

Literacy rates are expected to continue to grow steadily, according to new SDG 4 projections produced by the UIS and the Global Education Monitoring Report. At the global level, the youth literacy rate is expected to reach 94% by 2030 and the adult literacy rate 90%. Yet as shown in the figure below, in low-income countries, less than 70% of adults and slightly more than 80% of youth aged 15 to 24 years are projected to have basic literacy skills by 2030.

The most extreme challenges are seen in specific regions, with the lowest literacy rates found in Southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Southern Asia is home to almost one-half (49%) of the world’s illiterate population. While sub-Saharan Africa accounts for a far smaller proportion (27%), this masks literacy rates below 50% in 17 countries across the region (see the UIS e-Atlas on Literacy for interactive maps and charts).

Source: UIS eAtlas on Literacy.

One thing is clear: we need to know more about literacy – about who is learning the basic skills they need to thrive in school and in adult life, and about who is missing out (and why) – so that the first day at school is truly special for every child.

Note the date: On 12 September, the UIS will release new data on learning outcomes as part of its major education release for the school year ending in 2018. We hope that the data will show more rapid progress towards a world where every child leaves school equipped with the basic skills they need for life-long learning and prosperity.

Leave a comment