Thinking about studying abroad next year or know someone who is? You’re not alone. International student mobility is on the rise and data show that everyone benefits. Rather than depriving developing countries of their best talent through ‘brain drain,’ mobile students are offering ‘brain gain’ by creating a global pool of highly-skilled human capital.

As scientists and researchers, they are forming knowledge networks and increasing collaboration on global policy issues. This improves innovation in research and development (R&D) in host countries and generates results for countries that send students abroad.

When G20 education ministers meet from September 5-6 in Argentina, they will be focusing on the future of jobs, and the skills development needed to go with it. To help inform the discussions, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) has released a new paper, entitled Skills and Innovation in G20 Countries, which looks at skills development at different levels of education as well as the the impact of cross-border flows of students on R&D and innovation.

University students in Malaysia - Credit: World Bank

Most mobile students go to G20 countries

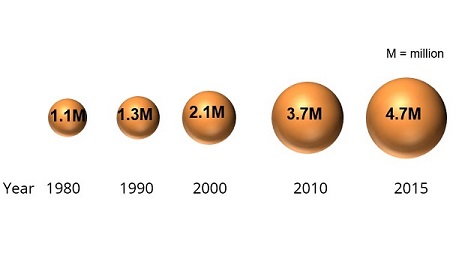

As enrollment in post-secondary education has grown, the number of students studying abroad has more than doubled from 2.1 million to 4.7 million in the last fifteen years (see Figure 1). UIS data show that two out of every 100 tertiary students pursue their studies abroad.

Figure 1. Long-term trend in the global numbers of internationally-mobile students, 1980-2015

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

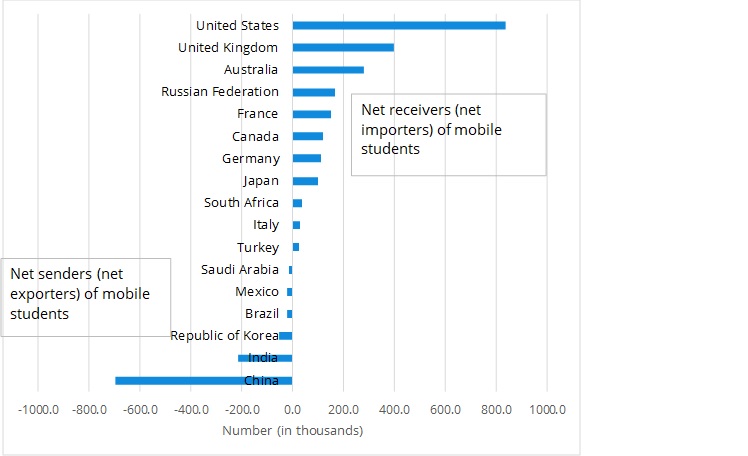

More than two-thirds of these mobile students live in G20 countries, with 19% studying in the United States, followed by 9% in the United Kingdom and 6% in Australia.

On the flip side, China is by far the largest source of internationally-mobile students with over 800,000 studying abroad in 2015. India, and to lesser extent Germany, also sends large numbers of students to study internationally (see Figure 2). In fact, a recent study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) suggests that due to demographic trends, India will soon surpass China in the supply of mobile students.

Figure 2. Net flow (inflows minus outflows) of mobile students by country, 2015

Note: Argentina and Indonesia are not presented due to a lack of data.

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

It is interesting to note that while China sends by far the largest number of students abroad, they account for just 2% of the total number of tertiary students in the country. In contrast, over 5% of university students in Saudi Arabia are internationally mobile. American students, on the other hand, are much less likely to study abroad with less than 1% choosing to do so.

All of this movement means that university campuses are becoming increasingly diverse. In the United Kingdom, for example, internationally mobile students account for almost 19% of the total number of tertiary-level students. Australia is a close runner-up with a foreign student body of 15%.

The rise of global knowledge networks

Both sending and receiving countries hope to benefit from this growing pool of skilled human capital. Host countries eager to build their own research capacities seek international talent. They vie for students by offering affordable, relevant, high-quality course offerings.

Sending countries, who may lack the capacity to educate students beyond secondary school, offer inducements such as scholarships so their students can gain innovation-promoting skill sets in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) subjects – and bring that knowledge back home.

Importantly from a gender perspective, while women now outpace men in overall tertiary educational attainment, they account for less 27% of all researchers in the G20, slightly lower than the global average. Only Argentina and South Africa have achieved gender parity.

Notwithstanding this imbalance, the accumulation of human talent within the G20 has created an impressive knowledge network. Global R&D activities and expenditure are concentrated in this economic region, mainly in the United States and China. However, collaboration within this vast talent pool – many of whom originated abroad – ensures that even the sending countries benefit.

When Ebola broke out in West Africa in 2014, for example, scientists, researchers and health professionals from governments, international organizations and the nonprofit sector worked together to find a solution. And, the UNESCO Science Report points out that climate change is another important area of collaboration as online global data hubs allow researchers around the world to compare work and bridge the gap between global and local efforts.

So, human talent flows can more rightly be seen as a brain gain for everyone: talented human capital that benefits host and home countries alike through collaboration on global issues. This network of internationally mobile students, and the scientists that they become, is arguably a public good.

International policy implications

Policies to promote education and innovation are a key part of global initiatives. The sustainable development goal for education (SDG 4), for example, promotes the expansion of scholarships available to students in developing countries for training in STEM subjects.

But, the significant rise in the number of internationally-mobile students has increased demand for course offerings. Out of the box solutions include online learning, foreign campuses and international joint degree programs so quality assurance systems are necessary to ensure that students are getting what they paid for. To this end, UNESCO and the OECD are developing a global convention for quality control.

When G20 education ministers meet this week, they may want to consider three takeaways for ongoing cooperation and policy initiatives.

In this era of rising student mobility and greater collaboration between talented individuals around the world, brain gain in science and technology is a net gain for everyone.

Leave a comment