By Silvia Montoya, Director of the UNESCO Institute for Statistics

After more than 6 months since the beginning of national lockdowns and school closures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, reopening schools is necessary and essential. Interruptions to classroom-based instructions have widened existing inequalities for vulnerable populations and reduced access to learning for a large fraction of the world’s children and youth. The longer schools remain closed, the more likely disadvantaged children are at risk of dropping out of school completely. Before the pandemic, children from the poorest households were already almost five times more likely to be out of primary school than their richer counterparts.

Proper infrastructure lacking to prevent the spread of COVID-19

As countries start to rethink how to address school openings, new national risk mitigation measures and public health regulations need to be considered within the school’s physical space. Children’s role in transmitting the coronavirus is still uncertain, and younger children are less likely to be sensitive or respectful of strict measures. As such, few schools are prepared to reopen in a way that can protect children, teachers and other school staff. Two of the most important measures cited by global health authorities to prevent the spread of COVID-19 – namely, frequent and proper hand washing (using soap and water) and social distancing – are highly dependent on the existing physical infrastructure.

COVID-19-related hygiene and social distancing norms in schools are unearthing a range of systemic problems with infrastructure in schools across the world. From European schools in densely-populated urban areas to rural remote village schools in the mountains of north-eastern Cambodia, schools are facing a wide range of challenges in their provision of adequately protective COVID-19 environments. Inadequate physical conditions, such as water shortages, poor sanitation and small classrooms, are proving difficult to overcome in the short-term for an immediate response.

Almost half the schools in the world do not have access to basic handwashing facilities with soap and water while one-third are lacking in basic sanitation (i.e. improved facilities that are single-sex and usable at the school). Overall, schools in rural areas fare worse than those in urban areas while children at the pre-primary and primary levels have less access to basic water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities than those in higher education levels. Younger children are more likely to be vulnerable to WASH-related diseases, yet are at the right ages at which to establish foundational learning around health and hygiene. Thus, training young children, staff and family members is an essential component to establishing WASH services for a community.

Establishing adequate WASH facilities for vulnerable populations is crucial

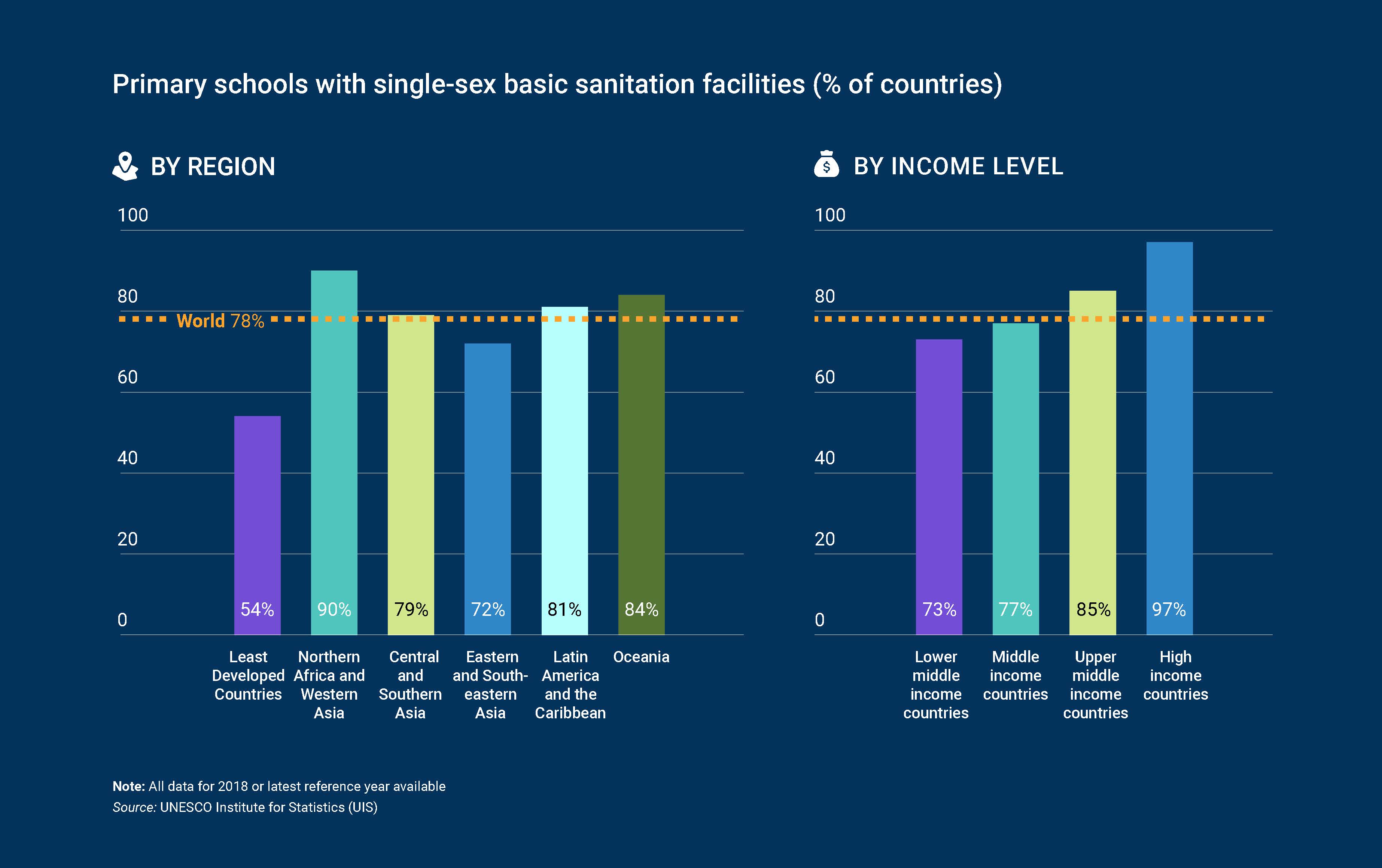

Basic WASH facilities in schools are particularly important for WASH-vulnerable populations, including girls, persons with disabilities, children from poor households and children living in fragile contexts. Access to water and sanitation is not only a right in itself as established in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child – and safeguarded by Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 – but it contributes to the realization of other child rights, such as health, nutrition and education. Girls require separate latrines as a fundamental part of their safety and healthy participation in life. Girls are more likely to enrol, attend and complete school if they have access to single-sex facilities, which are essential, particularly for menstrual hygiene management. Yet, this is only the case in 54% of the least developed countries, compared to 72% in Eastern and South-eastern Asia, 79% in in Central and Southern Asia and 81% in Latin America and the Caribbean (UIS database). According to World Bank ranked income levels, only 73% of lower middle income countries provide single-sex basic sanitation facilities to their female students, compared to the World average of 78% and 97% of high income countries.

In addition to WASH concerns, schools needs to consider the existing physical learning environment to safeguard social distancing norms. Adapting school norms to larger classrooms as a long-term response to the COVID-19 situation can also help establish quality learning environments in the long-term. There are no set international standards for classroom sizes or ratios, although norms and guidelines exist to provide guidance on better quality learning environments. In 2005, UNICEF’s Child-Friendly Schools Manual recommended a minimum 3.8 metres squared per child in early learning centres. Setting minimum spaces for children in higher education levels is more complex, however, and depends on the conditions of the local community (including projected population growth) as well as environmental and climatic conditions. In Rwanda, a minimum of one squared meter per pupil is considered adequate. One can also establish a basis for the overall classroom size, whereby child-friendly classrooms could reach a minimum of 100 square meters if playing areas and multi-activity classrooms are included. For example, the preschool square footage per student ratio is usually higher than for primary schools as younger children are less frequently required to sit still at their desks.

Global Education Coalition initiatives provides guidance

Changing or adapting infrastructure to meet the new demands, however, can prove an expensive enterprise for many countries. Indeed, the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) provided more than one-fifth of its total COVID-19 response grants (USD 266 million) to programmes in 12 countries that prepared school facilities for reopenings in safe environments for children and teachers. The Global Education Coalition for COVID-19 Response – launched by UNESCO in partnership with UNICEF, the World Bank, the World Food Programme and other United Nations agencies, international organizations, private sector and civil society representatives – developed the Framework for reopening schools. Reopening schools is composed of a three-step process (before, during and after reopening) and organised according to operational safety standards, learning practices, well-being and protection that reach out to the most marginalised populations (including girls). In addition to investing in WASH to mitigate virus transmission risks, the Framework aims to provide a holistic approach on safe operational procedures by including and training teachers and school staff in adhering to social distancing measures and adopting relevant hygiene practices. A more recent jointly developed update to proper procedures and checklists to consider prior to reopening is also now available.

Ensuring classrooms and materials are accessible and inclusive has been the cornerstone of quality learning environments, and such standards are well aligned with needs during the COVID-19 reopenings. For example, modular classrooms – where furniture can be moved, collapsed or put away – is already a recommendation in some national guidelines for classrooms. As children and projects evolve and change during the school year, spaces that are adaptive can reduce the density of students in the classroom as required by social distancing norms.

Some adopted measures can be detrimental to effective learning

Adaptations to small classroom spaces has been shown to provide less than ideal reopening environments in some countries. To maintain WHO-recommended distancing measures among students and teachers (minimum of 1 meter squared), many schools have limited the number of students returning to classrooms at the same time, thereby reducing effective classroom time for all students. In addition, WHO guidelines recommend several decision points with regards to school reopenings, with specific attention paid to local trends on COVID-19 cases. The guidelines in France, for example, adapted an approach that prioritised certain students (i.e. those of medical workers), followed by children from vulnerable families. Thus, the total amount of time returning to the classroom is a function of the strict social distancing requirements, the school’s physical infrastructure, teacher availability and children’s background.

As effective learning time is reduced for all students, a temporary response is to prioritise learning according to student needs. Limited time in the classroom can make teachers face more time-stress to meet the needs of national curricula and high-stakes examinations for certification or selection to the next education level. As part of the crisis-sensitive approach, education planners can reassess curricular objectives and transitions to upper education levels.

In 2015, the global community validated the importance of infrastructure to deliver quality education for all learners and teachers, regardless of background or disability status. The international standard noted in the Education 2030 Framework states that “Every learning environment should be accessible to all and have adequate resources and infrastructure to ensure reasonable class sizes and provide sanitation facilities.” Sanitation crises such as COVID-19 mark the urgency in reaching these goals and highlight existing concerns around poor learning environments. However, this moment can also serve as a catalyst to improve learning conditions and outcomes for all children.

Leave a comment