Sylvie Michaud, Chair of the UIS Governing Board and formerly Assistant Chief Statistician, Analytical Studies, Methodology and Statistical Infrastructure, Statistics Canada and Silvia Montoya, Director of the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS)

Thousands of policymakers, activists and researchers have gathered here in Canada for Women Deliver, which is the world’s largest conference on gender equality and the health, rights and wellbeing of women and girls.

The theme of this year’s conference is power and how it drives or hinders progress and change. For those of us who spend our days deep in statistics, information really is power. We believe that we must deliver data on women and girls if we are to help them reach their full potential. Gender equality is a key priority for tracking progress towards the achievement of all the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 4 on quality education for all.

If an education indicator can be broken down by sex, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) disaggregates it – from pre-school enrolment to PhD students, and from the percentage of women teachers to whether women researchers are equally represented in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) courses. If there are different trends for girls and boys at different ages as they make their way through the education system, we want to know why.

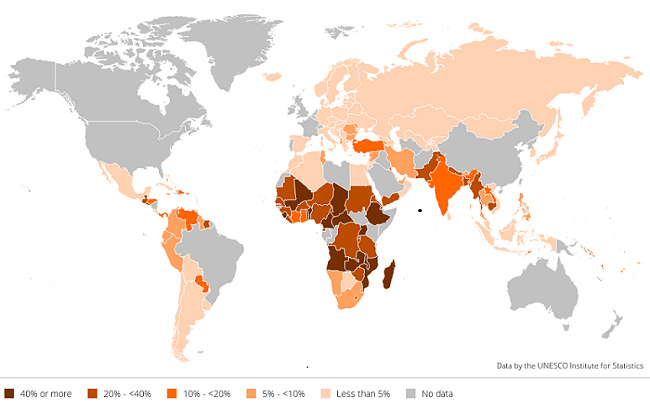

We carefully sift through the world’s data to see if girls are being taught in schools that are safe and supportive, with all the facilities they need. And if girls are out of school, we want to know where they are, how many of them there are, and why they are not in the classroom. The UIS has updated its eAtlas of Gender Inequality in Education to coincide with the Women Deliver conference. The interactive maps provide a one-stop, at-a-glance resource packed with data on all of these issues.

Figure 1. What percentage of girls drop out of primary school?

The conference will explore three aspects of power, each of which demonstrates the need to ensure gender equality in education.

1. Individual power

Education is critical for individual power. Until we have gender equality in education, it is hard – if not impossible – to picture a world where power is shared equally between women and men, and where the SDGs have been achieved.

Consider the benefits, which span every SDG, from poverty reduction to the creation of peaceful societies. Just one additional year of schooling can increase a woman's earnings by up to 20%. Education is also a safeguard against child, early and forced marriage, with the risks of early childbirth, violence and limited prospects: each year of secondary education reduces the likelihood of marrying as a child by five percentage points or more. And it helps to reduce child mortality: a child whose mother can read is 50% more likely to live past the age of five.

Overall, the world is moving in the right direction: the gender gap in education is closing and has been closing for decades. The majority of girls worldwide now complete primary school and we are close to gender parity at the primary level of education. Girls are also in school for longer than ever before. As 50 years of data produced by the UIS show, girls’ school life expectancy – the number of years they spend in school – is on the rise. 50 years ago a girl starting school in the world’s Least Developed Countries would receive less than three years of education. Today, she can expect almost nine years.

2. Structural power

We must address some major structural problems on the quality of education, as well as access. Worldwide, we have an estimated 617 million children and adolescents who are not reaching even the minimum proficiency levels in reading and mathematics. And we have 262 million children – one in every five – who are out of school.

Girls are less likely than boys to make the transition to secondary school in the poorest regions of the world, with barriers to their education that begin at the primary level becoming ever more difficult to overcome. If you are a girl from a poor family, living in a remote village or an urban slum, with a disability, or from a marginalised community, the barriers can become unbearable. As a result, just 2% of the poorest girls in low-income countries currently complete upper secondary school, and there are gender disparities in secondary education across the global south, according to the World Inequality on Education Database (WIDE), a joint product of the UIS and the Global Education Monitoring Report.

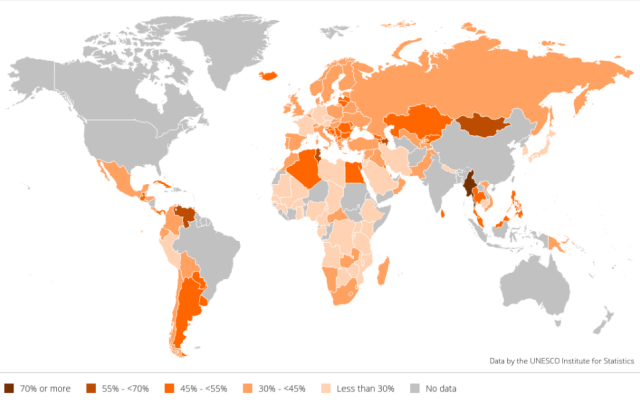

Worldwide, there are more young women than men enrolled in higher education – particularly in the wealthiest nations. But their numbers fall at the very highest levels of education, with far fewer women gaining a PhD and women accounting for less than 30% of researchers globally.

Figure 2. Percentage of women researchers

Part of the solutions lie in giving schools, teachers and entire education systems the power to deliver an education of high quality to each and every child. That demands equity in access to schooling and equity within the classroom, with girls given the same opportunities as boys to participate and to excel in all subjects. Education equity needs to be measured, of course – an area where the UIS has been working closely with national statistical agencies for many years.

One of the structural challenges that needs our diligent attention is to build the capacity of statistical gathering mechanisms and models – whether they are within the ministry of education or national statistical agencies – to ensure that developing countries are better able to gather, analyse, and report on girls’ progress in education and learning.

This is particularly important in conflict and crisis affected situations where war, instability, fragility and protracted conflict can limit a government’s ability to accurately gather and analyse evidence. Given that in conflict and crisis situations, girls are less likely to access or to complete their education, it remains of particular concern that we find ways to accurately gather disaggregated data and report on results.

3. The power of movements

SDG 4 emerged from a global recognition that education and learning are crucial for progress on everything else. The UIS continues to work with countries, technical partners and donors to produce the data needed to strengthen the education sector and ensure that every child is going to school and learning.

A leading partner of the UIS, the Government of Canada is one of the world’s champions for sex disaggregated data and gender statistics . In addition to supporting and hosting the UIS since it’s inception, the Government of Canada championed the endorsement in 2018 of the G7 Charlevoix Declaration on Quality Education for Girls, Adolescent Girls and Women in Developing Countries, which recognises that data and evidence help to empower women and girls to fulfil their potential and, therefore, helps the world deliver on its commitments to the SDGs. So we’re delighted that delegates from around the world are in Vancouver and hope that the Women Deliver conference will draw attention to the need for more and better disaggregated data and evidence to drive progress on education and, by extension, progress for women and girls.

Leave a comment