By Silvia Montoya, Director, UNESCO Institute for Statistics; and Alexandre Barbosa, Head of Regional Center for Studies on the Development of the Information Society, under the auspices of UNESCO, Brazil (Cetic.br).

The global provision of schooling is facing unprecedented challenges as a result of the COVID-19 crisis. Within the span of a few months, 191 countries had closed their schools to deploy social distancing measures in accordance with the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommendations. More than 1.5 billion students from pre-primary to university-level have been affected by these closures, with classroom-based learning interrupted for indefinite periods of time. While some education systems, teachers, students and parents were somewhat prepared to adapt to existing distance learning programmes and platforms, millions were not.

In the context of COVID-19 school closures, paper-based and digital distance education platforms have become essential to the continued provision of education for all. After more than a month of school closures across the world, many students are still struggling with remote learning. Global estimates suggest that 826 million students are without a household computer, 706 million lack internet access at home and another 56 million lack coverage by mobile 3G/4G networks. To better gauge the scope of the impact of school closures and of the ensuing national education responses, a survey of ministries of education developed jointly by UNESCO, UNICEF and the World Bank was recently launched to more accurately inform a collaborative global education response.

Without adequate information and communication technology (ICT) devices, internet/mobile network access, educational resources and teachers’ training, students simply cannot partake in distance education to continue on their learning trajectories. At most risk of being left behind are students from resource-poor areas, remote rural areas and low-income households. In addition, learners with disabilities or those who use a different language in the home than in school will require more individualised support.

Multiple delivery channels are an essential component to reach all children and youth during this pandemic. A recent UNICEF survey found that 68% of the 127 countries were using a combination of digital and non-digital delivery of remote education (i.e. TV, radio and take-home packages). Even before the COVID-19 related school closures, the use of radio, video and television for remote learning has proven to be strong components of well-designed numeracy, literacy and financial education programmes for children, youth and adults living in remote and rural communities. However, the implementation and reach of such programmes require the monitoring and support of trained educators.

Distance learning also requires that school systems consider the needs of parents and guardians who have to step in to facilitate learning to ensure the pedagogical continuity of their children, especially for the children in earlier grades (Grades 1-3) who need more one-on-one support. The ability for parents and guardians to effectively facilitate home-based learning depends on a variety of interacting factors, including their education level, native language and time availability. Understanding parental digital literacy – which could be estimated from SDG 4 Indicator 4.4.1 that assesses ICT skills among youth and adults – is essential for targeting skill support and development for parents. Without ICT skills support for the adults in the home, children from families with poor digital literacy are likely to fall even further behind.

Developing ICT skills to ensure education weathers the storm of future crises

Reports of parents, teachers, communities and networks that have developed innovative and makeshift interventions, such as mobile-based Wi-Fi networks as well as on-demand content and textbooks available in clouds -- to broaden digital capacities have certainly sparked optimism. However, these grassroots efforts largely serve as a short-term band-aid solution. Although they are inspiring, more fundamental developments to bolster access to and use of ICT are required – both at home and in schools, and especially for younger learners at the primary and secondary levels where gaps are largest. Hastily put-together remote teaching approaches have not proven to be optimal learning experiences and could be off-putting to some students.

School closures such as those currently experienced by the more than 1.5 billion students worldwide are commonplace in some countries due to natural emergencies, conflict as well as budgetary or labour negotiations. Once schools reopen, building skills and support for distance education in schools so learners can continue learning in the home can help minimise learning interruptions as well as deter learners from leaving school early or dropping out in the event of future crises. In addition, there remains a possibility that the COVID-19 crisis and its ensuing confinement measures may not be short-lived as flare-ups of cases may spark future school closures in certain countries. As some countries begin to reopen their schools, they will need to select innovative remote teaching modalities that blend with face-to-face teaching to ensure that learners are better prepared for future school closures. Thus, given the importance of distance education in the current context and in anticipation of future crises, countries need to take responsibility for monitoring, facilitating and enabling access to ICT in schools as well as in the homes of all learners.

Current measures of ICT availability fall short of capturing the needs in certain countries and regions as they fail to report on factors, such as the availability of electricity (grid- or solar based) and access to computers for pedagogical purposes, which are primary necessities. At a global level, these indicators are needed to monitor ICT use and detect national trends. However, they are not sufficiently detailed or policy-oriented to provide governments with adequate information to improve access to and use of ICT in education as well as sufficient information on teacher training and digital skills. For instance, counting the number of computers per school or per student poorly reflects the use of computers, which may in fact be minimal if these devices are locked in computer labs.

Monitoring ICT use in schools to better inform education policies post-confinement

Reliable data from school-based surveys can provide the quality ICT use data required to better inform education policy and practices, especially in developing countries. Capturing the complex set of factors involved will paint a more accurate picture of what is available and used by both students and teachers. This includes information, such as availability of digital infrastructure; internet connection speed; school activities in which teachers use ICT; training received by teachers to empower them to integrate ICT into their practices; strategies implemented by schools to develop digital skills; and perceptions by principals and teachers on ICT use in education and its barriers. Furthermore, the presence of qualified technical staff (e.g. technicians, librarians) is required to support the use of ICT in schools, including ensuring digital access and ICT learning among teachers.

These indicators and more are proposed in the Practical Guide to Implement Surveys on ICT Use in Primary and Secondary Schools – a joint publication by the UIS and Cetic.br (Regional Center for Studies on the Development of the Information Society). The guide discusses the relevance of survey data on ICT use in schools to inform policymaking and underscores the need for robust data to understand factors that determine equal access to and use of technologies by the teachers, principals, students and their families.The guide serves as an especially useful reference for government agencies, school authorities and other stakeholders looking to measure ICT access and use in education as it outlines the methodology and steps required to conduct a successful survey (i.e. planning, fieldwork, data processing, reporting and dissemination). This comprehensive document also examines the practical aspects of developing school-based surveys explicitly related to ICT and includes methodological datasheets for 26 core and optional indicators.

As some countries begin to reopen their schools, promoting equity in ICT access and use will continue to be an important factor to consider when addressing educational challenges for disadvantaged schools and learners from vulnerable households. In addition, the availability of computers, tablets, mobile phones and other potential learning devices, along with the provision of internet access in the home, will ultimately determine which children will be able to participate in distance learning and be more likely to complete their education in the event of future school closures.

Bridging the digital divide at home and in schools

Evidence indicates that there is a substantial ‘digital divide’ in access to ICT between countries. For example, according to estimates from the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), 21% of learners in Africa cannot be reached by 3G mobile networks. In terms of internet access, 82.2% of households in Africa lack access in the home (see Figure 1). To bridge the divide and encourage mobile-based education, and in addition to infrastructure investment, lowering the cost to consumers to gain access to online data needs to be considered as these are prohibitive in many countries.

Source: International Telecommunication Union (ITU)

Under Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 to ensure inclusive and equitable education and promote life-long learning opportunities for all, governments have committed both to increase digital skills and expand ICT infrastructure in schools. To support distance education, schools will need to better equip learners with the skills to migrate onto these online learning platforms. Moreover, closing the ‘digital divide’ will require governments to invest in supporting learners in the early grades of school. In this endeavour, the first step is to map within and between countries where investment is most needed. This requires better measures of access to and use of digital technologies in schools.

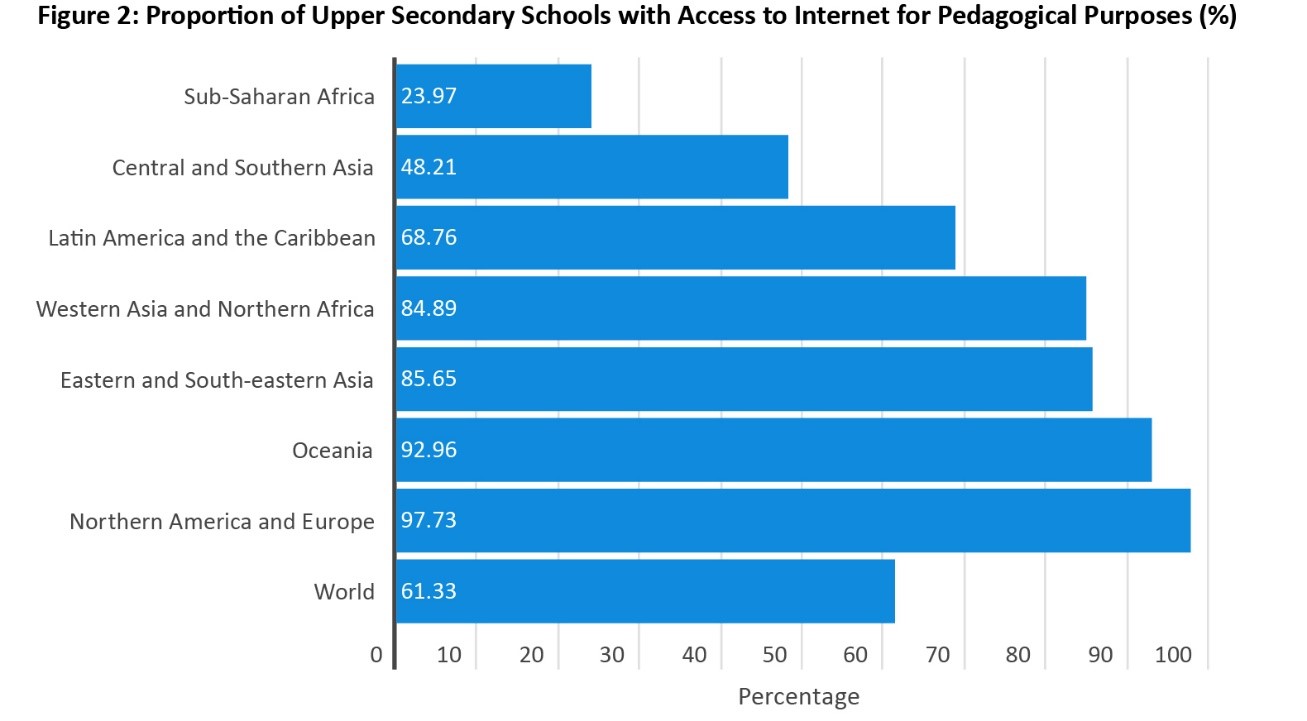

The latest UIS data for SDG Indicator 4.a.1 on the availability of electricity, computers and internet in schools for pedagogical purposes indicate that certain regions are behind in their capabilities to support learners. Although sub-Saharan Africa as well as Central and Southern Asia do not have sufficient data for this indicator in lower education levels, there is adequate data for upper-secondary schools. Only about one quarter of upper-secondary schools in sub-Saharan Africa and one-half in Central and Southern Asia are equipped with internet access (see Figure 2). Electricity – another necessity – is also not available equitably across regions and school levels. In sub-Saharan Africa, only 33.8% of primary schools have access to electricity while the same holds true for 57.2% of upper-secondary schools in the region. The situation is bleaker still in the Democratic Republic of the Congo where only 13.7% of upper-secondary schools have access to electricity.

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics, SDG 4 Data Explorer (data for the latest available year used).

Teacher training as part of the solution to closing the ICT skill gap

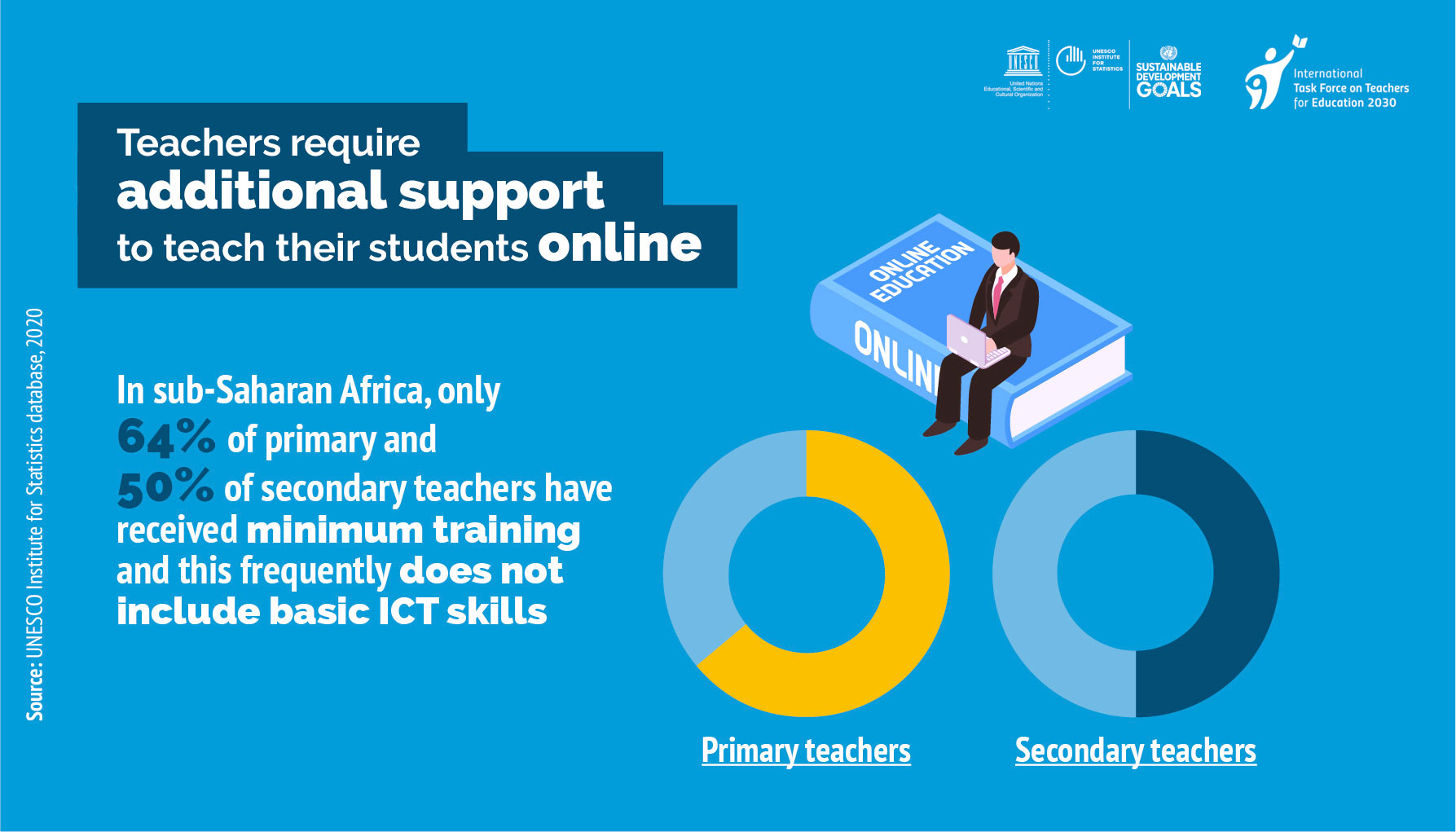

As noted, beyond the provision of internet access and ICT equipment in education, there is also a need to support learners by building their ICT skills. But what about teachers? During this period of school closures, teachers require training in the use of distance learning platforms to ensure teaching and learning can continue. While some of the 63 million primary and secondary school teachers who were displaced by COVID-19-related school closures have managed to reach students with their existing set of skills and equipment, many have not received basic teacher training. It is therefore disconcerting that most teacher training programmes do not include the use of ICT in education to develop appropriate learning and teaching strategies. In sub-Saharan Africa, only 64% of primary and 50% of secondary teachers have received minimum training. Indicators recommended in the Practical Guide to Implement Surveys on ICT Use in Primary and Secondary Schools can point to specific areas in which teacher training needs to be reinforced to improve ICT skills.

Leave a comment