New SDG 4 Data on Bullying

Share

01/10/2018

For the first time, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) has released data showing that almost one-third of young teens worldwide have recently experienced bullying.

The new figures are part of the annual UIS data release on progress towards SDG 4, covering 32 global and thematic indicators. The UIS has just updated its global education database for the school year ending in 2017, which includes historical time series, regional averages and indicators on a range of key policy issues related to school access, participation and completion by education level, learning outcomes, equity, teachers and education financing (see our paper on the release).

The new data show that bullying affects children everywhere. It ranges from a low of 7% of all adolescents in Tajikistan to 74% in Samoa and is pervasive across all regions and countries of different income levels. For example, 44% of adolescents in Afghanistan experience bullying, as do 35% of adolescents in Canada, 26% in Tanzania and 24% in Argentina.

The data on bullying were collected from in-school surveys that track the physical and emotional health of youth. The Global School Health Survey (GSHS) focuses on youth aged 13 to 17 years in low-income regions. Similarly, the Health Behavior in School-Age Children (HBSC) targets young people aged 11 to 15 years in 42 countries, primarily in Europe and North America.

The situation facing girls and boys

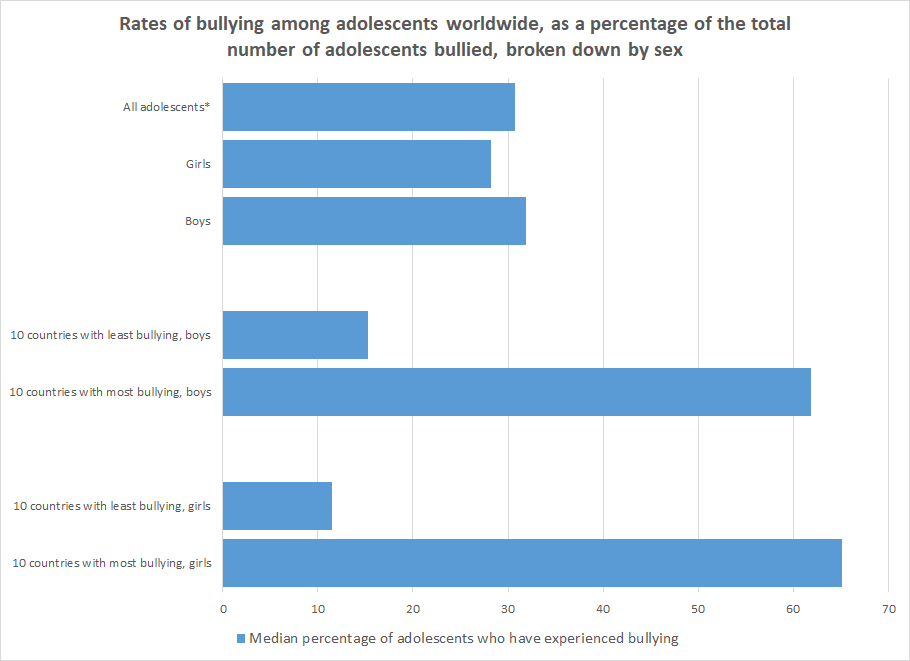

Globally boys are slightly more at risk of bullying in schools than girls. The data – which do not include sexual or other forms of gender-based violence – show that more than 32% of boys experience bullying in school, compared to 28% of girls.

Yet when looking at the 10 countries where children report the highest incidences of bullying, the median rates tell a slightly different story. In these 10 countries, a staggering 65% of girls and 62% of boys report bullying, revealing that where bullying is most pervasive, girls are more widely impacted.

External factors also have a role in bullying

Socioeconomic and immigrant status also play a part in bullying, according to the HBSC data on children from Europe and North America. In these regions, socioeconomic status – based on parents’ wealth, occupation and education level – is the most likely predictor of bullying: two out of five poor youth are negatively impacted. This compares to one-quarter of teens from wealthier families.

Finally, also based on the HBSC data, immigrant children tend to be more vulnerable to bullying than their locally-born counterparts. As migration around the world reaches new peaks, it is worth asking whether bullying will further complicate the ability of this vulnerable group to learn.

What are the main takeaways?