By Silvia Montoya, Director, UNESCO Institute for Statistics

World Children’s Day, established to promote child rights and welfare, is more important than ever this year as the world grapples with dual threats to education and health. Creating the evidence for policy actions to mitigate the impact of school closures is crucial, and for this, countries must assess children’s learning, along with the effectiveness of remote schooling, while supporting families, teachers and other front-line workers. At the same time, with keeping schools open being a priority, taking measures to ensure children’s safety in school is central to preventing further closures during a second wave of COVID-19.

From the beginning of the pandemic, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) has set the pace, collecting data on national government responses to the crisis, and collaborating with the World Bank and UNICEF on a joint report, What Have We Learnt. The report is based on two quarterly surveys – the first taking place between April and May with 118 respondents, and the second between July and October with 149 respondents.

The surveys confirm that students in low-income countries are most at risk from school closures. This is due to the fact that the larger number of school days lost and the perception (and perhaps reality) that learning from home does not have the same value as learning in the classroom, increases pressure on young people to drop out of school. Ultimately, only learning assessments will be able to tell us if remote schooling – online, TV and radio programming, as well as take-home paper-based work – have been effective. But in the meantime, 24 million students are at risk of dropping out this year, reducing their skills acquisition and earning prospects for years to come.

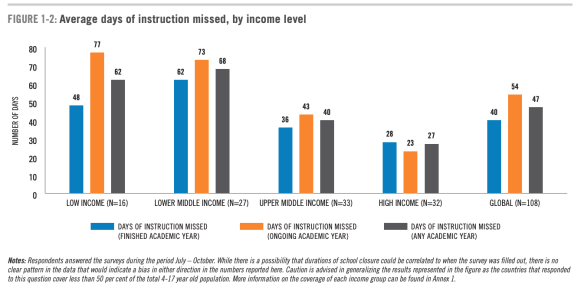

Diving into the data, What Have We Learnt reveals that globally, children lost 54 days of instruction, but in low- and lower-middle income countries, this rises to 77 and 73 days respectively, due to larger overlap of school closures with the academic year. A full understanding of the impact of these missed days will require learning assessments. However, our first survey revealed that more than half of all respondents opted to postpone or reschedule assessments such as national examinations.

Pursuing this issue in the second survey round, we asked governments more specifically about plans to track learning. It turns out that teachers in a quarter of low- and lower-middle income countries were not tracking learning. In high- and upper-middle income countries, 3% and 8% of teachers, respectively, were not tracking learning.

Research points out that the pandemic has likely caused a decline in learning for children in Grade 3, globally, with the proportion of those proficient in reading falling from 59% in 2019 to 50% this year. Whether or not this learning loss for third graders continues depends on the impact of the disruption on even younger students, including those registered in pre-primary education this year. This research suggests that catching up to the 2019 proficiency levels may not occur until after 2030.

It is crucial that countries and development partners work together to build capacity for learning assessments. This is because well-designed assessment programmes create evidence on learning losses and inform mitigation strategies. This year, assessing learning will also be a proxy for the effectiveness of remote teaching modalities. As such, they will contribute to our understanding of how remote learning can build resilience in education systems while preparing for future crises.

Globally, What Have We Learnt notes that online and TV programming were the most widely deployed means to reach students stuck at home during shutdowns. However, online learning was much less popular in low-income countries where just 40% of students have access to the internet. Globally, online learning occurred across 90% of countries, yet only in 64% of low-income countries. On the other hand, TV programming was much more pervasive in low- and middle-income countries, even though lower TV ownership among rural households would have made it harder, if not impossible, for children in these areas to access lessons.

This is reflected in the perceived effectiveness of remote learning options in low-income countries. Respondents in low-income countries perceived a lower effectiveness for online, TV and take-home forms of remote learning compared with governments in other income groups; only radio was considered to be slightly worse in upper-middle and high-income countries.

Beyond assessing learning and analysing the effect of remote delivery, What Have We Learnt examines how countries plan to mitigate learning losses, along with health measures they plan to take to keep COVID-19 at bay.

On the front-line of the education crisis, support for teachers and families will be the key to keeping children safe and healthy throughout the second wave. Already some school districts – such as New York City – have announced plans to return to online learning as cases of COVID-19 rise.

This World Children’s Day, we all have to do our part to keep each other safe while giving children a chance to stay in school. For us, this means supporting countries’ efforts to assess both learning and the effectiveness of remote schooling options and building evidence for informed responses to this intensified learning crisis.

Leave a comment